When Google brought its monorail to my campus

Plus some things to ask when they come to yours

In a recent LinkedIn post, Ben Williamson responds to “Google’s work in schools aims to create a ‘pipeline of future users,’ internal documents say” (Tyler Kingkade, NBC News, January 23, 2026), writing that “They said it, though many of us having been saying for a while they were exploiting education through educational subscription contracts and customer-pipeline lubricants.”

In the US, Google builds at least brand familiarity if not brand loyalty through pushing Google Classroom and Chromebooks to school districts. But they’re not stopping at K-12. Their active pursuit of higher ed customers – students, instructors, and institutions – has involved courting faculty and administrators for years. With the AI Revolution (their words, as you’ll see below), they’re taking the show on the road. While I am sorely tempted to adopt Williamson’s lubricant metaphor, I think I’ll go with the monorail – at least in part because they are leaning heavily into FOMO to sell teachers and institutions their product door to door, as it were.

I’ve been meaning for a while to write about Google’s trip to my own campus last fall. They were brought in as part of an Ed-School-organized AI week called “Falling into AI.” Before I start, I want to say that I think folks at my university, like educators everywhere, are trying to make the best of a new tech landscape, even if many of them have taken a different path than I have in doing so. And I will also say that there is nothing particularly new about ed tech companies pitching their wares to educational institutions.1 However, I’m very much not on board with a company with whom we have no formal relationship being stirred into an ostensibly research-and-teaching-based event with hours on end of sales pitching. And no, Google, repeating “this is not a sales pitch” does not convince anyone that it’s not a sales pitch. Even the AI enthusiasts in the audience mumbled “it’s a sales pitch” every time their reps said it wasn’t (and they said it A LOT).

As one approached the student union in which the first of the week’s events had been scheduled, one could not miss Google’s presence. They had set up a tent, staffed by enthusiastic young college-aged students, offering free access to Gemini Pro for a year. When I asked the workers whether I, as a faculty member, could also get free access, a friendly staffer chirped “I don’t know why not!” and encouraged me to scan the QR code. And indeed, I could get free Gemini Pro – the usual month trial which would expire unless I provided documentation that I was a student.

Google: “Come on in, kids! The first hit is free!”

Inside, as the “kickoff” to this AI week, Google offered a “keynote” for the first hour delivered by “Jeremy and Chris.”2 These reps were, to me, interchangeable, a similarity amplified by tag-teaming and shared messaging. The description of the keynote online promised that “we will also discuss the alignment of these initiatives with the strategic goals of KU’s AI Taskforce” – which, unless I had a blackout at some point during the event, was not part of the conversation (and indeed, as a member of said AI Taskforce, I had specifically asked that Google not have a public-facing event without first meeting with us.)

Instead, Chrisemy bounced through a slide deck while sharing little of substance other than a fragmented and somewhat incoherent version of the usual marketing spiel for genAI tools. The keynote is available online, so feel free to assess it yourself if that’s how you want to spend an hour of your precious time in this world. But to me, it felt like they were not prepared for a keynote that should have been easy as (a) pie (chart) for Google for Education brand reps to deliver.

An example:

Some kids and a phone for some reason. Pretty clouds! Unreadable pie chart! Sewers! Android!

When this slide popped up, Chrisemy launched into this incisive reflection.

More people have access to generative AI than they do sanitary wastewater solutions. Is that shocking to think about? … Google has 74% market share on the the mobile device market globally. I think about an Android in the hands of more people than that have a septic system or have the sewer. More people have an Android phone. And we’re giving this technology to them. So it’s something that we need to take seriously because if we don’t and we’re not focused on solving problems using these tools, it’s available to everyone, someone else will. So I think today is a great and this week is a great forum for us all to share our ideas and work together and figure out how we can all have a bigger impact locally at KU and, you know, across the world.

I take this from the transcript, which I double-checked with the video. This is, I would say, an exemplar of the quality of the almost hour-long presentation - not a sales pitch! - and at the very least not a particularly compelling advertisement for the next-level clarity one can achieve partnering with Google AI.

Soon, we got to this insightful slide:

The AI Revolution is here - accompanied by AI-generated 90s hotel hallway décor, apparently.

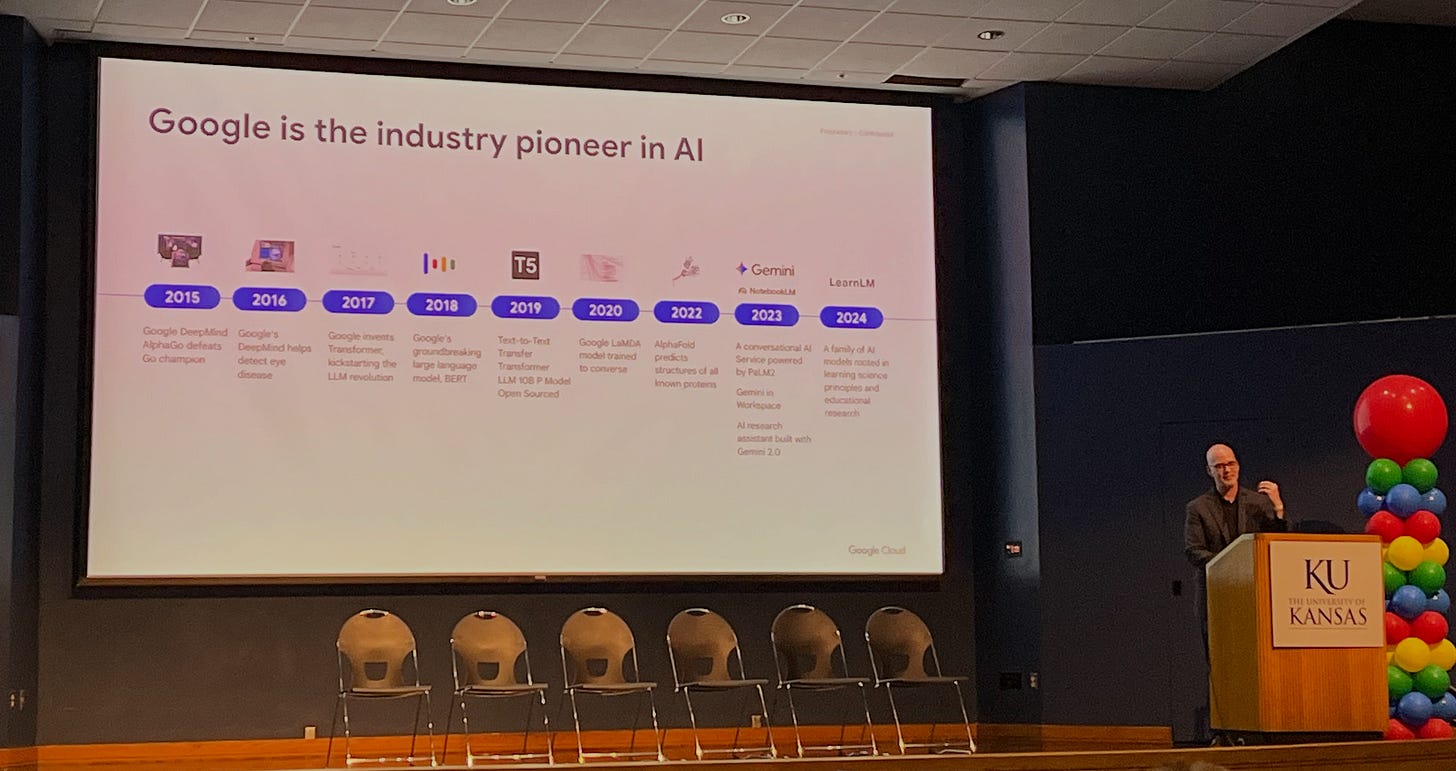

When he advanced to this slide, Chrisemy said, both jokingly and seemingly sympathetically, “I don’t know if you’ve heard. AI’s here. You didn’t have a choice, by the way. None of us did.” That latter is quite a claim to make before, a few slides later, he shared this:

“None of us” had a choice, even though “us” were the industry pioneers in AI?

Someone had a choice, clearly.

There were a lot of claims and random stats shared. Early in the spiel, for instance, Chrisemy claimed that “we have a reclamation goal of 120% that we actually produce more water than we take in from our data centers. I’m not sure how that’s possible, but that’s our stated goal.” Yeah, I don’t know either, man. But I trust you.

Throughout, “Nano Banana” (the Google image generator released the previous month) was repeated like a verbal tic despite its irrelevance to the ostensible topic. Which was not a Google sales pitch, I promise.

After that keynote – no time allotted for questions – students were herded off to a different room to speak to Lanley or whoever.

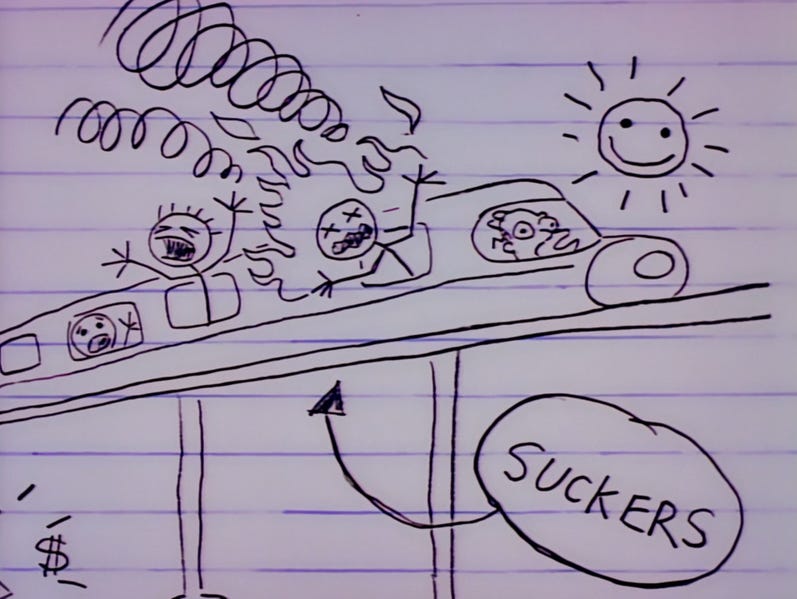

Lisa Simpson: Why build a monorail in a small town with a centralized population around a town center?

Lanley: I could answer that question for you, but you and I would be the only ones here who would understand the answer. (leans in) And that includes your teacher! (Image: screen capture, “Marge v the Monorail.”)

Some faculty and staff who didn’t wander off to other breakouts remained in the auditorium for a “fireside chat” in which Google reps sat in front of an AI-generated fire answering softball questions with the coherence normally associated with people surprised out of a nap.

There were, after almost 2 hours of this, approximately 12 minutes allotted for questions.

I was not called on, but since I had my hand up from the start, a person behind me asked to see my handwritten question, and after reading it, photographed it and promised to take it to one of our administrative colleagues who was in contact with Google. Here’s the question I had hoped to ask:

I teach critical AI literacy. I notice that you have tents outside and you, along with a few other tech companies like OpenAI and Perplexity, are offering free access to subscription AI services to students but not teachers. You noted in your presentation that students are already using it. It seems to me, given the risk of learning loss and use issues like hallucination to consider, it would be wiser at least to offer teachers the tool free first to help guide students on when and whether to use those tools. Otherwise, it looks like you’re promoting a vision of education without educators or pushing for us to get an enterprise license to keep up with students. Can you comment on [your decision] to provide students free access and not teachers first?

Perhaps it goes without saying that I had a lot more questions. This one did get to Google via my administrative colleague, and when that colleague asked me to provide more context, I wrote back to him at length. The relevant parts of the email follow:

I’d have liked the opportunity for them to respond publicly, which is why I was one of the first people to put up my hand. That said, it would be interesting to see what they say, even if it isn’t public.

You’ve asked for context, so I’m shaping my response for you; apologies if you know all of this already. Google has recently joined OpenAI and Perplexity in an arms race for market share to get students using their tools. OpenAI and Perplexity both are doing the same thing: a year free for students. (Perplexity also offers Comet, an AI agent, which can go into an LMS and complete assignments for students without them even looking at it. Google is also rolling out agents.) These tech companies know (and have data to show) that their tools are used most during the ends of semesters, when students are writing papers and taking tests. Since their (and every other tech company’s) investments in AI have outstripped returns, they recognize education as a huge potential market. Google does have a potential edge because lots of high schoolers are familiar with it through Google Classroom. (Google Classroom switched on Gemini over the summer; schools have to opt out rather than in).

Why wouldn’t they have offered free trials to schools or teachers? Interestingly, apps like MagicSchool and Khanmigo (that embed foundation models from Anthropic, OpenAI, and others) did offer free licenses to teachers, but that was because they knew their tools might provide shortcuts to overworked high school teachers.

On the surface, it would appear likely that they are hoping that we would buy an institutional license in part to encourage us to “keep up” with our students’ use.

I’d add that the reps deeply misrepresented something yesterday. (Well, more than one thing, but this is particularly relevant to the conversation at hand). They mentioned that Google launched “Homework Help” to a select group of people but then took it down when they realized it was helping students cheat. But that’s not true: the “select group of people” was anyone who updated Chrome. None asked for it; many still have it. And for those who don’t, it still exists as Google Lens, and still will answer test, discussion, and homework questions for students who are, for instance, in Canvas. I tested it last week. So what their reps are claiming about what they’re prioritizing in terms of education doesn’t really align with the company’s actual practice; it instead aligns with the bottom line, which is to grab that market share of students.

I’d add that I do appreciate that they have a slightly more “conservative” approach to IP violations in training their systems; that said, they trained on the entire corpus of published work in Google Books. If they really cared about privacy and IP, they’d protect IP and data robustly without an institutional license. Requiring an enterprise license to protect our and our students’ data and IP is, frankly, rather like the mob asking for protection money.

I know a lot of folks want us to buy a Google license. I am not denying that there are tools that, with guidance from critically informed instructors, could be valuable if you are willing, as many apparently are, to set aside the considerable ethical issues with the tools.

If they want our business, they should give teachers a sandbox first.

This message was apparently forwarded to Victoria Spielberg (known only as “Victoria” in the listing on the page describing the event, but who according to her sig file is “Chief Strategist, Higher Education & GovTech”). Her reply:

Thanks for sharing this feedback. I appreciate you bringing these concerns to our attention. I’d like to address some of the points raised in Katie’s email.

First, I want to clarify that Google for Education offers a wide range of free tools and resources for educators, not just students. In addition to the free Google Workspace for Education Fundamentals, we also provide professional development resources, training, and various programs to support educators in using our tools effectively. I’ve included a link to our main resource page for higher education institutions, which details many of these offerings, including career certificates and other programs.3

Regarding “Homework Help” and Google Lens, I understand the concern about tools that could potentially be used for cheating. “Homework Help” was an experimental feature that was indeed discontinued. Google Lens is a visual search tool that is part of our public-facing Google Search and is not specifically designed as an educational tool. We are constantly working to improve our tools and welcome feedback on how to make them more helpful for both students and educators.

Finally, on the topic of data privacy and IP, I want to assure you that we take these issues very seriously. For our Google Workspace for Education users, we have stringent privacy and security protections in place. We do not use customer data for ad targeting, and we are committed to protecting the intellectual property of our users. An enterprise license provides additional administrative controls, security features, and support. Our commitment to privacy is a core part of all our education offerings.

Hopefully, this helps. Students are becoming savvy with using tech to cut corners. Not all, but some. I use Google Lens to help me identify pictures of plants and mushrooms, find where to buy something I see, or diagnose bug bites on my kids. I certainly hope it doesn’t go away :)

Alas, it did not “help.” But there, my readers, is where I left it. Note the lack of a response to any of my questions or context. Note the sidestepping of the questions in particular about their misrepresentations, and their effective admission that “stringent privacy and security protections” are only for paid users.

And side note: I hope to hell Victoria isn’t using Google Lens to feed her family mushrooms.4

So, in the interests of providing more than LOLsobs, I’d like to offer you some more things you can ask if Google, OpenAI, Perplexity, or other representatives show up at your school.

For all AI-based edtech companies (the big ones plus Brisk, Flint, MagicSchool, SchoolAI, etc): OpenAI has admitted that large language models “hallucinate” – that hallucination is baked into generative AI systems. [see for instance this article] And as experts note, those mistakes are plausible, don’t come in the same places as human mistakes, and can’t be mitigated in the same ways. Why should educators, researchers, and students ever be using a technological system that will always potentially insert mistakes that are often hard to catch, even for experts?

There have been a lot of studies that show negative cognitive impacts of generative AI use – cognitive offloading isn’t necessarily always bad, but arguably not what we want in an educational environment. There have also been studies showing reductions in retention after using LLMs for tasks, reduction in critical and creative thinking, and so forth. How do you recommend mitigating the kind of learning loss that seems to result from systems like yours? [Check out some of these studies here under “Cognitive Impacts,” and share newer studies in the comments!]

Could you share with us whether all of the datasets on which your AI models are trained come from consensually obtained, licensed, or public domain materials? [Note: if they like Mira Murati use the term “publicly available” in reference to their data, note that that is not a legal category, and publicly available material still has copyright]

Follow-up: Kevin Gannon, in a recent Chronicle article, writes: “Either we have copyright law or we don’t. Either plagiarism and the theft of intellectual property are anathema to higher education or they aren’t. We’re either modeling academic honesty and integrity to our students or we aren’t. … GenAI’s architecture absolutely depends on consciously taken actions that would stand in violation of any of our institutions’ academic-integrity policies.” Could you respond?

Alternate follow up: Could you explain why we have to pay for enterprise licenses for your intellectual property but you don’t have to pay for the intellectual property you used to train your systems?

Is all student and faculty data guaranteed to be protected in all of your systems and also not used for training ? If not, do we have to make a special deal or licensing arrangement to ensure that protection? Why is it not already protected?

For companies that have partnered with the military (OpenAI, Google, Meta): Do you have an AI safety team for your education division, and is it the same safety team that oversees your collaborations with the NSA and the US military?

Whatever questions you have, ask them. If you can’t ask the companies, ask the folks in your IT team or administration who are responsible for purchasing technology licenses. Let’s normalize expecting at least as much clarity and honesty from the tech companies with which we’re expected to do business as we do from our colleagues and students.

“I’ve sold monorails to Brockway, Ogdenville, and North Haverbrook, and by gum it put them on the map!” Image: From monorail huckster Lyle Lanley’s notebook, courtesy of Wikisimpsons.

See especially Audrey Watters, Teaching Machines, and also check out “Ed tech is profitable. It is also mostly useless” in the recent Economist.

They were identified only by their first names online, perhaps to make them all seem more approachable; none of the Google representatives’ full names and titles were shared in the online program. Afterward, I watched the video again to catch their quick introductions and looked them up: Chris Daugherty, Education Strategy Lead, and Jeremy Dautenhahn, Google Public Sector.

Victoria linked these sites in her email but if you want to find them, you can Google them!

AI mushroom identifications have been increasingly implicated in poisonings. Here’s one story about Google Lens in particular: “I was recently tagged by one friend in another friend’s Facebook post. ‘Hey Jack, Look at this! How cool!’ What I saw was not cool. It was disturbing. The original poster had stumbled across a large flush of new mushrooms, from buttons to fully mature cap and stems. They got out of their car, used GOOGLE LENS (notorious for its bad IDs by the way) to identify the flush of mushrooms. Google lens not only misidentified the mushroom, but gave it an edibility rating of ‘Choice edible.’ The ID it gave was Macrolepiota procera. The actual mushroom was Chlorophyllum molybdites, AKA, ‘the vomiter.’ Eating just one cap of the toxic C. molybdites can make you very ill, but my friend and their spouse ate a whole pan full of caps and stems. Yep, they were seriously ill for many miserable hours.” https://fungimag.com/v17i2/v17n2-Claypool.pdf

The list of questions at the end are THE questions.

Not surprised Silicon Valley predators were not particularly helpful in answering them